A key aspect of what the House Poetics project is trying to do is to understand how and why we may group things together; from objects in our daily lives to people and social occasions. A big part of that revolves around understanding associations between artefacts found together in an archaeological ‘deposit’. Using the word ‘deposit’ implies intentional action, that things were purposefully placed together, although as archaeologists we acknowledge that often (more often than we like), it is very difficult (if not impossible) to be certain of this kind of intentionality in the contexts we encounter. It’s also a matter of what we may consider belongs together not just through spatial association (found nearby), but through conceptual links; e.g. we may think plates and cups belong together to make up an eating-and-drinking assemblage. But as anyone who has reorganised their book or CD collection (I know this is showing my age regrettably) would tell you, there are so many infinite variations of making associations between things. I am regularly reminded of that when looking for a research article in my pdf library; is “Birth, death and Motherhood in Ancient Greece” to be found under “Death and burial”, “Gender”, “Kinship”, Classics” or all? This is not simply about knowing where to find a book (even in my antiquated filing system there are easy and efficient search functions), but it is essentially about the topologies of research: depending on what I am researching and writing, I may need to include it in a different ‘assemblage’. And let me tell you, plenty of our chipped coffee mugs now belong to the ‘water-colouring implements’ assemblage…

I was trying to get these ideas across a group of lovely 8-year olds at a primary school. They were learning about the Roman Empire and so I organised a mock dig to get them a) to enjoy archaeology by getting mucky (their teacher was less enthused by the prospect of sand everywhere, but was brave enough to allow it), and b) to think how we learn about the past through the things we find in the ground. The digging part was great fun, if not a little unruly with everyone trying to unearth the biggest chunk of whatever was in my magic dig box. When it came to interpreting the ‘finds’, it was quite a different story; they were understandably more thrilled by the complete pieces of my Roman ‘treasure’, but soon they got quite excited about figuring out what the broken objects would have looked like and what they might have been used for.

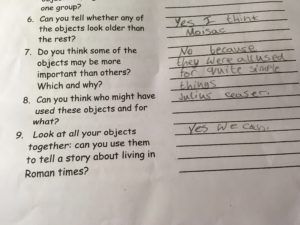

The most interesting aspect of the exercise though was when I asked them to make up a story with the objects they found in their boxes. Storytelling as a way of learning was familiar to them (if a little underexplored) through their classroom study and it proved an effective way of engaging with the objects. However, even allowing for some of their more deadpan answers (which actually made me seriously reconsider my teaching techniques!), their ‘assembling’ of the finds into a narrative was quite lateral, going off ramp into directions that perhaps have been rendered invisible (or difficult to imagine at best) to us through our institutional and professional training. I put this down to the kind of categories we learnt to work with and how difficult it is to ‘think outside’ those categories in our engagement with archaeological materials and interpreting social life in the past. It also proved to me the value of being creative with our reconstructions of the past: surely, Julius Caesar might not have used this particular clay lamp on his way to catch giants so that they would make this huge mosaic floor for him (if a Hollywood producer is reading this, I sadly cannot take credit for this scenario), but how wonderfully this joints all these disparate artefacts into a vivid (and not too implausible reconstruction). They decided to call their efforts “ A story out of the box”. This made me happy on so many different levels.